At least, it's new to me. And it's also new in the sense of being different from other training pots - different enough to be granted a patent. The pot is made in Austria by an outfit called "Kristen & Zahalka", possibly the patent holders. I bought mine online from Stone Lantern, a vendor I consider worthy of repeat business. (More on both a bit later.)

The manufacturer simply calls it a "tie pot." One look at a picture and you see why: those knobs all around the outside rim are made to be anchor points for guy wires.

|

| A "tie pot" for bonsai-in-training. |

Guy wires can be very useful for stabilizing a tree while its roots re-establish themselves after repotting. This is especially true with cascade-style trees, whether semi- or full-, because their weight can be seriously one-sided. Sometimes anchor wires from below simply aren't enough, or in the right position, to keep the tree at the planting angle you want while it re-anchors itself. I have a semi-cascade 'Tigerbark' fig (Ficus microcarpa 'Tigerbark') of which this is true: if it's not guy-wired from the side after a repotting, its lopsided weight will topple it right out of position (and sometimes out of the pot!)

Guy wires can also be useful when shaping a bonsai-in-training. Sometimes a guy wire can pull a branch into position as effectively as wrapped wire. It can be left in place for years without danger of significant scarring, a consideration useful with trees that take a long time to set in a new position, such as ponderosa pine. And if a guy wire is thin it is much less noticeable than wrapped wire if the tree is displayed.

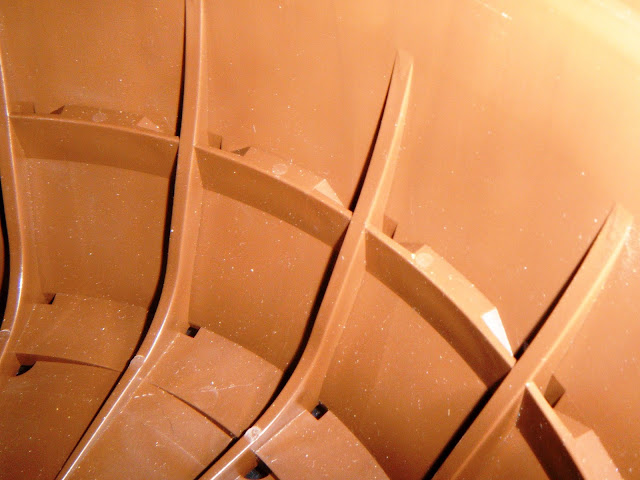

|

| Close-up of the anchor knobs. |

The knobs are sturdy: when my pot arrived I tested them with my fingers, and they aren't going anywhere. That's important because, whether a guy wire is used for anchoring or for shaping, it goes without saying that a reliable anchor point is essential. There are 18 knobs around the circumference of the pot, spaced about two inches apart (roughly five centimeters.)

The whole pot is sturdy, made from high-impact plastic. I tried flexing the pot wall between my hands, using a good deal of force, and it would just barely flex. In normal bonsai use it won't flex. This matters because if a pot wall flexes, the soil mass inside it gets flexed; that means that the roots inside the soil get flexed, and that means broken feeder roots, because roots aren't made to flex like branches are.

These pots are also designed to promote air-puning, another worthy feature. For any who don't know, "air-pruning" is the term for what happens when a root grows out into the open air. The exposed root tip dries out and dies, and the plant seals it off. Then the part of the root still in the soil branches to the sides, and voilà, you are that much closer to a compact, well-branched root system close to the trunk. And because the old root tip is sealed off rather than cut or broken, there is no break in the root's surface thru which pathogens can enter.

I'm sure most of my readers know what a plant's roots look like when it's been grown in a standard round, smooth-walled nursery pot. The roots grow out horizontally until they hit the wall of the pot; then they grow down to the bottom. Then, once they can go no deeper, they start to circle round and round at the bottom of the pot. The result can look like a clump of long-strand spaghetti!

These pots break that sequence with a system of internal low ridges to stop the circling, and holes to guide the root tips out of the pot for air-pruning. Take a look at the next two pictures:

|

| Internal ridges to guide roots down to holes to the outside. |

|

| A closer look at the system of ridges and holes |

Notice the narrow shelf running around the inside of the pot, about two inches above the pot floor. Notice that wherever that shelf is intersected by a ridge, there's a little ramp on either side, leading down like a funnel. Those "funnels" guide the rootlets to openings to the outside, as the next picture shows.

|

| Root tips that enter the side holes (previous picture) emerge from these downward-facing openings. |

Forgive the blurriness of the next picture, but I don't have a better one. I held the pot up to the early-evening sky to show just how many holes the bottom of the pot contains. All those holes give root tips access to the outside air. The eight largest holes that form an inner ring should also serve adequately for drainage. They are each only about a half-inch across, but there are eight of them.

|

| A view against the sky to show all the holes! |

I haven't yet had my hands on both the pot and my tape measure at the same time, but I can say the pot's diameter is very close to 8 inches at the bottom and 12 inches at the rim. Internal depth is about 4 inches. I estimate it will hold between one and one-and-one-half US gallons (roughly 3½ to 5 liters). Here's a picture with a standard 12-ounce beverage can right in the center.

|

| 12-oz. beverage can for a size reference |

Stone Lantern is one of those vendors that I recommend in the sidebar; for their website, click here. Wayne Schoech and his crew sell a wide range of bonsai-related supplies, and I've never been dissatisfied with anything I've bought from them. For the English version of the tie pot manufacturer's website, click here. They sell other pots besides.

Obviously I have yet to grow anything in my new pot, but I expect it to live up to the claims about it. And I believe I have an appropriate candidate for its first occupant: this dwarf yaupon holly (Ilex vomitoria 'Schilling') that I got last summer in a workshop with Adam Lavigne of "Adam's Art and Bonsai." If any of tree of mine will need guy wires to keep it stable after repotting, this will be one. Look at that hollowed and twisted lower trunk!

|

| Dwarf yaupon holly, first in line to spend a year or two in the tie pot. |

Give me a couple of years and I'll write a follow-up post on my experience with my new container.

:-) :-) :-)